Discover more from BASKETBALL FEELINGS

A new conduit for empathy

Where does grief fit in fandom? On Johnny and Matthew Gaudreau, Aaron and Drew Gordon, and the body keeping score.

We learn about the accident as we get back from walking the dogs. I’m rattling kibble into bowls as the countertop speaker starts to rattle off the news. George pogos and Captain pulls a few quick, tight spins before lying down like a sphinx, panting. We had them down to Mount Pleasant cemetery and back before the sun was skimming over the tops of the Beltline’s trees.

The CBC radio host says the name Johnny Gaudreau and from the other side of the kitchen, measuring coffee into the filter basket, Dylan says, brightly and reflexively, Johnny Hockey! We go silent as the host finishes delivering the news, killed along with his younger brother, Matthew, when the two were struck by a car while riding bicycles in New Jersey last night.

George barks. I realize I have not set the food down. Over the dogs crunching gulps I hear the word investigation, I hear the phrase suspected drunk driving. I wait the seconds it takes for them to finish their breakfast then rinse the bowls and fill them with water. Dylan comes back into the kitchen from retrieving his phone from another room and says the two brothers had been in the town they were in for their sister’s wedding, the next day. Now today. He reads me as much news as there is at that point.

The reaction I have is the kind you do when you hear news that is so tragic, so senseless, so abruptly and violently ceasing of one reality into another which has not yet taken hold but is approaching, fast and irrevocable. The normal words used to describe this kind of news, like tragic and senseless, feeling very cheap, like thin, brittle plastic. Something that will yield at the barest pressure. But those are the words we have.

I didn’t follow Gaudreau’s career. I knew his name via proximity when he played for the Flames, and from hearing it lobbed by hosts on sports radio shows I’ve been a guest on as I waited, muted on a switchboard, for the segment to shift to NBA basketball.

It takes me days to realize why I feel so strangely bereft over the news. Beyond the public empathy for loss that seems too great, larger than what real life should bear, I feel a deep down stilling in the pit of my stomach whenever I read or hear or think about the two of them, peddling into the plummy, shifting dark of a late-August evening, likely laughing, maybe calling over a shoulder to the other, or maybe just quiet and content knowing they are together, pulled tight in the orbit of family and occasion, flush from the air and the blood working through their bodies but flush with something deeper, too. Suffused with the security that comes with family, whether the bonds you’re born into or the ones you make for yourself. The feeling like a forcefield.

It takes me more time still to answer the question I am fielding from a critical chorus in my head, a mix of, Why do you feel so affected by this? and, This isn’t your grief. A guilty feeling in assigning any understanding, or ownership. Whether this is performative grief. The chorus parades, loops back around, trumpets This didn’t happened to you, until a much quieter voice — my voice — finally recalls, almost in surprise, It has.

My own accident, different (alone, late in the fall, west end Toronto) and all too similar (struck from behind at speed, in a bike lane, the driver drunk). The sinking feeling that I keep getting is the same tinge I feel whenever I pass a ghost bike chained up around the city, nearly ubiquitous in some neighbourhoods. It’s the same cold stalling out when I read on Twitter or overhear a conversation or see a ticker go across CP24 about a cyclist being killed by a motorist. What’s that saying, the body keeps score? There’s a residual feeling that comes with trauma, especially the sort that you excavate in layers, and wind up burying again.

For a long time — and likely still partially given the mental chorus I mentioned — I felt like my accident was something to move off from as quickly as I could. Pursuing legal action was so far out of my or my family’s processing that it took a school friend of my brother’s, who worked in a firm and heard about what had happened to me, suggesting to him we should talk to someone and then making the appointment for us to even go down that road. That process was a long one, years, and “winning” still feels like the wrong way to put it. There was surveillance from the driver’s insurance company as I got my life back on track: went back to work, got back on my bike. It made me a less credible victim. There was the worry that I’d see the driver who ran me over in court and how that would feel, and then the inappropriate but still funny realization that how would I recognize him? They’d pulled me out from under the car and I woke up in the hospital.

Writing about the process and putting it into a wider context years later helped me assign greater sense, some logic, to what happened, but I remember a person I was close to around the time of the accident responding to the piece: You aren’t over that yet?

He meant it — I can soften in retrospect — as a joke. A bad joke, yes, but lightly. We were young and he was younger, bravado over vulnerability like a crude roadwork patch job. The irony, and strange connection that remains, is that he was a sort of sliding door. I met him earlier the night of the accident and there was a spark, an invitation. If I’d lingered, the accident doesn’t happen. Maybe it happens to someone else. More than the what-ifs, which are ultimately pointless, his framing stayed with me. Stays with me still. As a flash of doubt, secondhand embarrassment, when I see a white bike festooned with fake flowers at an intersection I use all the time, or heard about Johnny and Matthew Gaudreau being killed by a drunk driver, outside of any realm of familiarity. These seizing flashes of emotional and bodily repose to tragic, senseless, abruptly violent deaths.

Do they have anything to do with me? From my brain: No. From my body: A very pronounced stillness. Something deep and dormant, perking up. An accordioning of time. Years into yesterday. The damp smell of leaf litter, an ease in my muscles that always comes after spending time with my brother, the solid, capable feeling the metal teeth of the bike pedals pushing into the worn soles of my Vans gave me.

The body keeps score but you’ve no idea the reckoning.

There’s a vulnerability to Aaron Gordon. Something open. I’ve watched both him and the quality grow more confident since he’s established himself in Denver but more realistically, since he’s continued to gain significant years in the league. Not in small part because with those years have come disappointment and an at times blunt, forced shifting of perspective. Gordon went from a one-dimensional high-flyer to a rarer thing, a connector up and down the floor. His game slowed down. He learned to watch and wait, he learned there was more competitive longevity in playing dynamic, playing a role.

Gordon had the capacity to play this kind of game in Orlando, but in his tenure there he had five coaches over his first six seasons in the league. With every head coaching change comes not just a new voice giving direction, but a complete cleaning of house. From assistant coaches to trainers, even equipment managers, personnel shift and with them goes the rhythm of the team. Given that, and in retrospect, it’s not surprising that Gordon fell back on what was most familiar to him: dunking and its pageantry. Dunking and its forced recognition. Dunking and its readymade persona.

Gordon’s vulnerability, sometimes manifesting as caring very much about something, has made people uncomfortable. We don’t want for our athletes to openly want things so badly, the perfect mix of stoicism and bravado must always be struck. Desire as a slow simmer is best, too much plain pining, or eagerness, becomes thirsty, corny. An example of Gordon’s open want I always come back to, maybe because I was in the room, was the gamut of bare emotion he went through after losing the Dunk Contest at Chicago’s 2020 All-Star Weekend. In his postgame presser he was cocky, he was hurt (he was also physically hurt — his wrist and arm swelling in real time), he’d switch from deadpan to animated, he vowed to never compete in the contest again with a voice full of reticence and disbelief. He said he didn’t care about the result and then he released a track two months later railing against Dwyane Wade for his poor judgement in the competition, replete with a music video.

In Denver, with his change of role and more succinctly, stability, there came a new appreciation for Gordon in part because he appeared to “settle down”. His desires, on the surface, became restrained. We knew better what to do with him when we were told he was a role player now, because we have flattened role players to only want what the team does. That’s as far, we say, as their desire reaches, and we love them for it. Selfless, we say. Singular.

Moreover, there was less dunking, sometimes none. While there was certainly maturation in the way Gordon honed his skills, when the Nuggets won their title he had been in the league for a decade. Is it envy, the reason we ascribe dunking to juvenility? It isn’t just the understanding that in aging, we know bodies shed their easy kinetic force, because we want and still expect to see people like LeBron James perform as LeBron James. James dunks, it’s worth noting, but he has always done it with a cool control (there’s never been anything of longing about the way James plays basketball — the chosen one, after all).

I learned only recently that it was Gordon’s older brother, Drew, who inspired his explosive tendencies. Five years older than Aaron, Drew was a cyclonic athlete. Powerful and strong, a bit larger than Aaron, Drew was bound to his physicality by virtue of his size but also the competitive climate he played in. His heyday was filled with eruptive bigs: Blake Griffin, DeMarcus Cousins, DeAndre Jordan; Anthony Davis was drafted first overall in 2012, the year Drew declared for the NBA but went undrafted. By the time Aaron was drafted, Drew had played for six professional teams, in the U.S. and internationally, and would go on to spend time in the NBA and abroad, putting together a professional career that spanned 12 years and 10 countries.

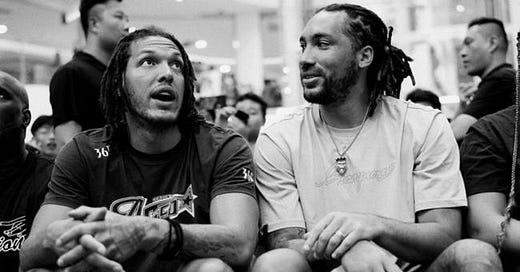

Watching his brother from his rostered spot on the Magic, having achieved this dream his family wanted, I wonder if there was an added restlessness in Aaron. He had stability on paper, but the plans for him kept changing. His brother had none of that but he had his independence and the certainty of what he continued to sign up for as a mercenary athlete of size and drive. I wonder how much Aaron watched, emulated, sought their shared physical traits as an anchor.

I wonder too, when Drew retired in July 2023 after Aaron won his first title with the Nuggets, if it didn’t have something to do with the sense of Aaron “settling”. Whether in us projecting onto him or an actual shift in his awareness. Drew, the globetrotting grinder, moved with his young family to Oregon. He began coaching AAU and launched a sports management company with his and Aaron’s older sister, Elise. The Gordon family was settling, finally, all in the same country.

Drew Gordon died at the end of May, his vehicle colliding with another on a two-lane stretch of road south of Portland. It was just a week after the Nuggets were eliminated from the playoffs.

Aaron Gordon announced this week that he’s changing his number from 50 to 32, the number Drew wore. The Nuggets posted about the change and a few days later, Gordon posted a short video of himself dunking, landing, and tearing his jersey down the middle to reveal a second jersey underneath with the number 32. The clip is only around 15 seconds long but it made me think about the leniency we afford public figures, and certainly athletes, in grief. The desirous, open vulnerability of Gordon, within the parameters of grief, is something we understand what to do with.

The timing isn’t lost on me either. If the Nuggets and Gordon chose to wait until, say, media day to make the announcement, there is the worry of it overshadowing everything else that might come out of it. Never mind that NBA media day is mainly a warmup exercise for fandom (though I appreciate the thought I hope the team had, in sparing Gordon multiple questions about the choice to switch numbers, about Drew, about grief, in his allotted 10-ish minutes on a very well-lit podium before or after the team’s social media staff pull him away to film a goofy video). Waiting until closer to the season might also stir up the weird panic and response in the kind of fans who view anything but basketball, and athletes being anything but basketball-minded, as distraction. Even grief. I can picture very clearly the comments. No disrespect, but he needs to focus on the season.

Or, He’s not over that yet?

Is it that grief is such a severe, disruptive feeling that it stuns us? Is that why we’re able to offer unrestrained, honest empathy to strangers, including athletes? Athletes for whom we typically fit into exacting and precise frameworks, suddenly made whole and human in loss. The kind of empathy delivered without strings, timelines, or parasocial attachment. A necessary connection we understand for a flashing or sinking few seconds to be very human, as natural to wield as it is essential.

It’s important to interrogate our own feelings. Especially so when they’re projected or overlaid across another person, known to us or no. Having gone through something similarly horrific, or plain bad, as someone else doesn’t lend an automatic, emotional clairvoyance, but it can carve out a new conduit for empathy. Empathy you don’t want for its price, but in it’s truest sense — em- as in, and pathos, feeling — of inhabiting a feeling, its precursors and aftermath. To recognize what your body remembers and to extend the best you can towards what it might yet be lucky not to know.

Maybe your feelings about the accident are hard to move on from because it is so violently frustrating. Cyclists getting mowed down by aggressive or distracted drivers is just becoming commonplace and with laughably minor repercussions. How that changes seems impossible sometimes

This is a really amazing piece, thank you.