A softer world

Seeking out softness in the space between basketball's arbitrary binaries, and in the day-to-day.

Since I’ve been home, and more in the past week, I’ve found myself seeking out softness. Visually, by letting my eyes blur over the jocund piles of pumpkins spilling out of milk crates and stacked high in cardboard boxes in front of the neighbourhood’s fruit markets, their curves and lumpy ridges so affably tactile just to look at. Watching videos of my nephew in the bath my brother sends from Kochi, his eyes widening as Carl slowly swishes him through warm water, a smile finally poking into his big cheeks. Squinting up at how huge and luminous the clouds here have been all week, hanging out at the edges, giant and cream white against the deep cerulean of an October Toronto sky — a blue of its own quality, a last gasp blue.

Physically, by digging my fingers into the thick fur around Captain’s neck as he lies in a spot of sun, picking up (and putting back) huge bunches of tangerine, beetroot red and cotton candy pink dahlias from the florist’s big plastic paint buckets, going dizzy from blowing up balloons too quickly to litter around the living room for Dylan’s birthday.

On the bus, looking up from my book for a minute to watch the heads and shoulders of everyone else riding jostle and sway in time with the bumps. How susceptible our bodies to larger forces, like giant potholes, our vulnerability all synced up.

I catch myself leaning back and sideways like a painter eyeballing a canvas, getting eye-level with the birthday cake I’d made and was icing, turning it carefully on the stand. Something about covering every trace of sponge with vanilla buttercream so rewarding, slowing, that rather than leave a couple spots sparse when I finished I made a whole other batch of icing.

Someone drives by blasting Brian Adams, Rod Stewart and Sting’s ‘All for Love’ from the Three Musketeers and I stop writing, literally shut my eyes and hold my breath. The urge to mutter wow at myself comes, then passes. Adams’ plaintive cry fades into traffic.

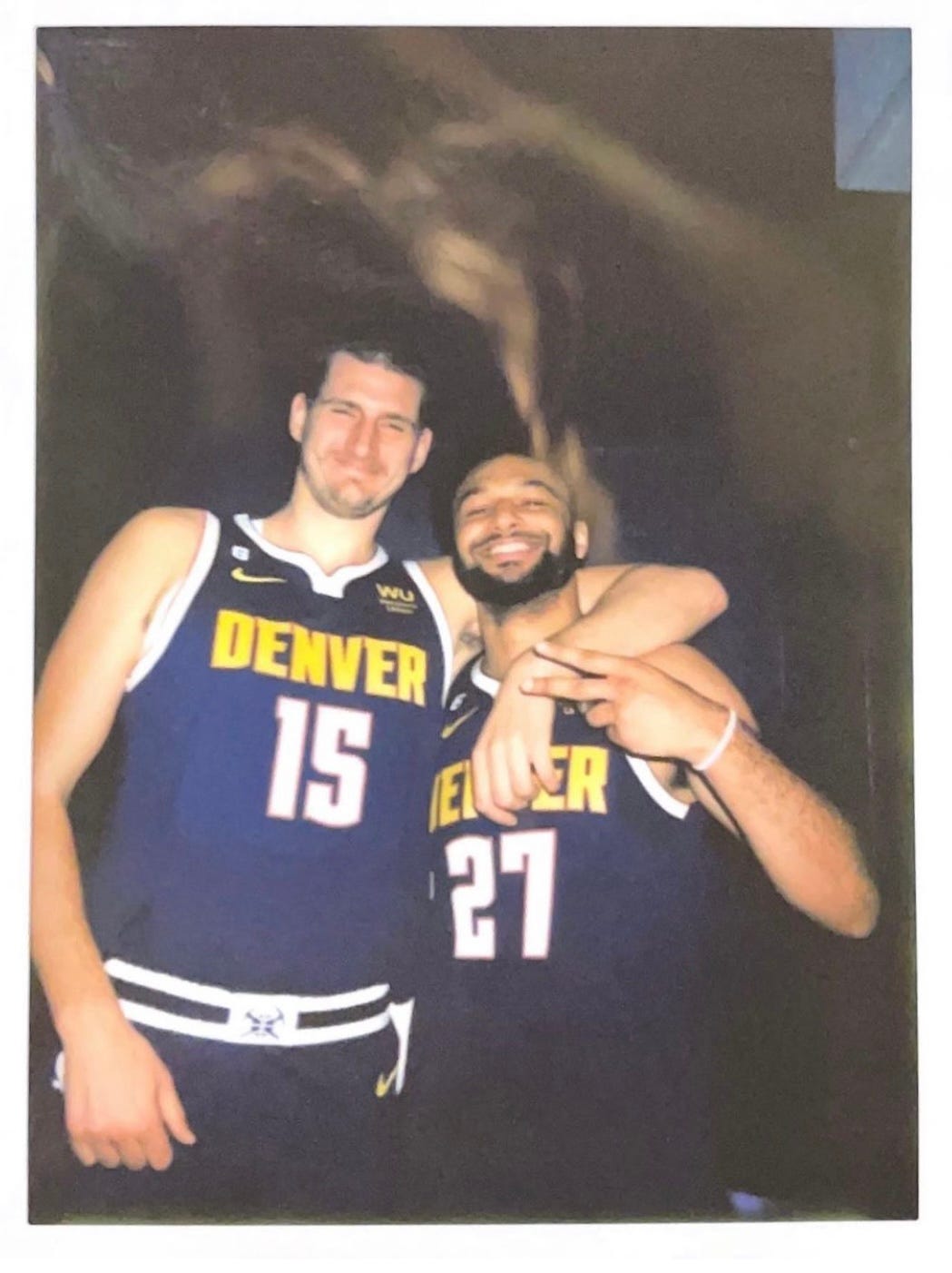

I ask Jamal Murray, maybe to the chagrin of the corporation the interview was through, about a photo he took with Nikola Jokic just over a year ago.

A compositional outtake, out of focus with exposure or damage on its upper half that looks like tendrils of light coasting down around the pair. Jokic has one giant arm hooked around Murray’s neck, pulling him snug against his side, his lips pressed together in an eyes-squeezed-shut smile, the kind you make when you’re so happy you don’t care how you look. Murray is grinning, teeth showing but not showboating, flashing a peace sign and easy under the weight of his friend. The photo cuts Jokic off at the thighs and Murray at the hips. Everything around them is pitched into fuzzy black that the two glow bright against, like a source of light.

I bring the photo up because I want only to talk about the photo, how joyful and tender and easy it is, and because I can’t really bring myself to talk about basketball in a concrete way, in a way that feels like it matters in the moment we’re talking. A moment where, 20 minutes before it, I had been scrolling through horror after abject horror reported out of Gaza, all more immediate than the impending call and immediately diminishing.

Murray had just finished practice. I could hear the ambient sounds of the gym. Voices bursting loud then fading, ricocheting. His breath, not catching, but his voice full and clean in the way a voice is when the lungs have just cycled through so much oxygen and blood.

I want only to talk about the photo, but it’s an interview so I mention the photo and then ask about duos. That rare relationship in sports that can turn intuitive or hostile, depending on how long it lasts and the outside world’s probing and pressures. Before he answers that part, Murray seems to sense my subterfuge.

That photo is framed and hanging in my house, by the way, he tells me. He sounds proud. If I can be nosy, I say, after he’s talked about their partnership with one another, Can I ask where it was taken? It was Media Day, Murray says. I joke that I’m not sure anyone looks so genuinely happy on Media Day and Murray laughs. It was a good day, he says.

Later, I’ll think of how when we got started and I said, Hi from Toronto, Murray asked if it was cold here yet. I looked at the afternoon’s bright sun flashing from the waxy leaves of the skinny oaks out the window, still green, and said it was that beautiful time in fall where it lulls you from what’s coming. Just around the corner, he chuckled knowingly. How on a day in a week where all tenderness and compassion, curiosity and care towards strangers seems to be evaporating, this one little probe gave me hope.

Softness can be the space between arbitrary binaries, the hard lines we tend to grow most comfortable operating within.

If you don’t side with one thing it doesn’t make you automatically aligned with the other, but in a world where the strongest global powers have made themselves that way through violent dominion then our rhetoric, our very thinking, tends to follow. Tends to fall in line.

In basketball, the stakes are much lower. Held up to the atrocities of this week and there are effectively none. But the thing basketball’s binaries have in common with geopolitics is that at their most severe they spring from human origins, that is, the fundamental feelings that make up the experience.

Fear is a big one. It’s embedded deep in the language of “busts” and the hard binary of the Draft. A top 10 projected rookie’s a generational phenomena or they’re wiped from the collective minds of fandom if they don’t wow in their first season. Never mind that the most impactful athletes who wind up with the longest careers tend to come in the middle and take five or more seasons to find their fit. That these are the people who we tend to make our favourites because of how they’ve rejected the hard binary of bust or instant success, how they’ve persevered in the middle space with so much room to roam, grow, fail and figure it out free of the pressure made in extremes.

Fear’s in the thinking of “title or bust” for a team, though I wonder if anyone, given a rational beat to reflect on just how much has to break perfect for titles to happen, actually believes this.

Fear’s in the way we talk about injuries. First in the hushed tones live commentary will drop to when someone is hurt, lifting when the person rises from the floor, either by their own power or with help. Then comes speculation, also edged in fear. That the person won’t “come back the same”, won’t come back at all, in most cases before that person even knows the full extent of what’s happened in their own body. Fear allows us an arms-length of intellectual distance to speculate about bodies strange to us.

It strikes me that most of the joy in basketball, at least what I can confidently call on right now, comes from dwelling in the softness of its in-between stretches. Some — the seeming suspended verticality of a dunk, the celebration after — last seconds, while others — rooting for a team on the margins with no stakes that plays electric and wild most every night — can last for seasons.

The vulnerability of intent in a tunnel fit, the gentleness we get to catch when guys hug a little longer after the last hard loss in a long series, the cocky lightness of trash talk between friends facing each other from opposite ends of the floor, an errant pass getting scooped up and run away with, chasedown blocks that come on like rolling thunder and crash like a summer storm, finally arriving. When the Bucks boycotted Game 5 in the Bubble because of the murder of Jacob Blake, how Sterling Brown and George Hill’s voices sounded when they read what the team had written on paper scrounged up in the already makeshift locker room, simultaneously tentative and sure, gutting and critical to hear it, a clarion call galling that they had to make at all.

These bookends to the action of the game, beautiful little blips in basketball’s metred movement — there’s a reason they give us chills, make us choke up or laugh or emit a kind of mangled merger of the two. They’re the moments that take us out of rhythm and remember what it is we’re watching. How dramatic, impressive, notable. How thrilling, fun, plainly just cool. These are also the moments, I’ve found, that athletes like to talk about, whether they were difficult, like Brown’s, or sweet, like Murray’s. Probably because they stood out to them for the same reasons: they slowed life down to the immediate.

If some of the game’s most callous characteristics come from our worst impulses as people, then many of its bests come from the times we opt for the in-betweens, the unknown. When we reject the rigidity of a binary to remain vulnerable without rushing to don the armour of extremes, delay falling neatly behind the fixed understanding of one-or-the-other, and lull in the rarity of a softer world, briefly opened up.

You’ve summed it up exactly. Thanks for giving voice to the coping mechanism I too am employing now. It’s been a week of mourning still spent savoring the small moments of joy.

At one time or another, this photo has been my lock screen. Changed it back after reading this. Thank you.