Entire universes, within the waiting

The intimacies, vulnerabilities, and hierarchies of waiting, in and out of the NBA.

In Spanish, espera, from Galician-Portuguese esperar — to hope — from the Latin spero, an anticipatory tense closer to “awaiting”, the sensation of it. In Italian, attesa, a feeling of expectation. In Japanese, the kanji radicals for “wait” (待) include soil (or earth, ground), measurement, and stop (or linger, loiter). The Norwegian vente derives from venir (come) and te (to you, yourself). The German word, warten, takes its origin from “to wake” or “to watch”. In Farsi, sabar kon, with sabar taken from the Arabic for patience, and kon, a present tense verb for “to do”.

We have, for a long time, considered what it is to wait.

On the platform in Salerno we are staring down the tracks, willing the train to come. Dylan has jogged down the stairs to the tunnel that runs under each platform three times to get to the station entrance. The main monitor there is the only one displaying a chronological grid of arrivals information. The screens mounted to the concrete columns of the platform we’re waiting on only urge us to please, stand by.

Before we got there, disembarking our train into the unexpected chill of a morning several degrees cooler from where we started thanks to the Alburni mountains and the winds that roll down them to the sea forceful enough to keep the clouds away (and what keeps Salerno, I’ll learn later, one of the sunniest cities in Italy), we were stuck in a tunnel. A problem on the tracks ahead, the conductor informed everyone.

Was Salerno our final destination, the porter who’d checked our tickets asked. No, we were catching the Frecciarossa to San Giovanni. She pursed her lips and considered it, glancing to the windows where the three of us were reflected back. I think you will be fine, she concluded, but if you are late for this, come and find me. We don’t ask how we’d find her across the eight train car if we were late, and whether this moment of realization would come before we disembarked, or after and she continued on with the same train.

On the platform in Salerno, our first train has chugged away and there is no trace of the second. People all around us seem to be picking up their bags and moving to other platforms. I show the ticket on my phone to another porter. She puts both hands out in front of her, palms down, and gently pats the air. Just wait, she says.

We do as we’re told not because we feel confident the train, now late, has not come and gone without us, departing from any of the other platforms where trains have pulled in, exchanged a flurry of passengers, and pulled away, but because we are in thrall to the act of waiting. To the determined, immobilizing sensation that comes the longer you wait for something and the certainty that the moment you stop, when you give up and leave, the thing you are waiting for will happen. In our case, arrive.

I think how willing an outcome through waiting is a shoddy sort of manifesting, given all the possible outcomes that reel through your mind as you wait. I think of both porters. How in their instructions they wisely extricated themselves from the act of our waiting.

Without fanfare, the giant red Frecciarossa speed train silently pulls up to the platform.

Working around basketball, you get used to waiting. Waiting for people, waiting for games, waiting for people to prepare for and finish games.

It was the first complaint I heard when I started to cover the sport and is still the one offered most, at times in the quality of pleasantry, an eye-rolling commiseration. As in, so and so isn’t out yet? In some cases, so and so is an entire team and you are waiting for them to wrap up shootaround or practice, for locker rooms to open.

The complaint can be made to a room of media, waiting for a coach to walk in, it can also be made in arena tunnels, on courts, standing around in a loose knot of bodies where a scrum will soon take place and tighten the formation up on invisible cue. It can be hushed, delivered just to you; it can be spoken loudly but in feigned secrecy, the hope being that someone might hear and hurry things along. It never hurries things along.

I don’t mind the waiting. For one, there’s lots to watch or listen to in the liminal space it creates. In pressers and workrooms there are other people, also waiting, who fidget, zone out, gossip loudly on purpose or by accident, who might be happy to chat as you both wait. There are also the people not waiting, who work in the wings of what’s happening and move with purpose in and out of these rooms and hallways, hauling equipment or rolling carts of food or speaking furtively into earpieces and phones. In locker rooms, well I’ve learned to listen more than watch, a delicate line there between privacy and availability, and an added awareness being a woman being watched for how I navigate an intrinsically male space.

Waiting on courts and walking through tunnels is some of my favourite waiting because it’s where the strictly chanced moments happen. Run-ins, off-hand introductions, flurries of social pockets. Right-place-right-timing it. This waiting can also be, despite all the people caught up in its function and routine, solitary — and necessarily so. A breather to go stand or sit somewhere, to gather your thoughts within controlled chaos.

There is power in waiting, a feeling the act of waiting tends to wring out of us. I’m reminded of it the times I’ve been made to wait on the job, when an athlete veers to either end of the spectrum of waiting. At one end, when guys spend what feels like hours in the showers, or linger in treatment rooms waiting for media in the locker room to give up and clear out. At the other, when Russell Westbrook changes so quickly he’s out of the locker room before it opens after the game, and I went running after him down a tunnel.

In her book All Things Are Too Small, Becca Rothfield writes about the way waiting speaks to power. Namely, who has it and how the act of waiting puts us into positions where we expect to subdue time or are in turn subdued by it.

“If women historically have been the ones who wait, it is at least in part because most cultures have confined them to a state of involuntary idleness,” Rothfield writes.

The gendered distribution of waiting assumes a hierarchy of time and activity in which men set the terms and fix the schedules. To be waited for is to assert the importance of one's time; to wait is to occupy a position of eternal readiness in which one can be called on at male convenience. Waiting amounts in this sense to "waiting on": waiting women exist provisionally and subserviently, in the service of an absent element.

I’ve felt the gendered distribution of waiting as a low, background thrum for most of my life. From domestic tasks and whose work-life schedules take priority at any given time, to career timelines, to the way I’ve witnessed men in my life expect not to wait.

I’ve wondered if the extra waiting athletes make media wanting to talk to them do is to wrest back a sense of control, consciously or not. I’ve never felt particularly ruffled the times I’ve been made to wait, but I have felt a kind of probing in the waiting. I’ve also wondered if I’m “better” at waiting, or at not taking it personally as I’ve seen some do, because of that low-grade, consistent awareness.

Waiting is always a little bit intimate. We associate waiting at its most pure, or romanticized, with heightened awareness. It’s anticipatory, even in frustration — you’re piqued. In total vigilance.

The critic Hans-Jost Frey wrote in his book Interruptions, "To understand waiting as expectation is to think of it from the point of view of totality. One who waits is in a state of incompleteness and waits for completion."

It can be as simple as waiting for a game to start, or for a date in the future you’ve pinned expectation or hope on to arrive (a vacation, a birthday) even something more dire (a breakup) or mundane (the bus to show up). Through the waiting, you assign yourself into a state of suspension.

To return to Rothfield, and waiting as a sort of tender power, she writes, “Waiting is the ultimate act of vulnerability: it requires a willingness to endanger one's wholeness, to halve oneself.”

In waiting for athletes, this vulnerability is myriad. There’s the unspoken rules of any given social exchange (if you ask a question of someone in good faith and within fair parameters, you expect a considered response), and the literal rules of the league (players are obligated to be available either pre or post game). There is entering into an intimate space (the locker room) or a hostile space (not always, but taking a seat at a table on a dias or at the front of a room with rows of people facing you isn’t automatically natural), and reading them. There is knowing when to push, when to back off, when to be candid, and when to keep it short. There’s adrenalin and fatigue, and two different sets of emotion serving as backdrop to the waiting.

To be aware of all of this, as it’s happening, is to have known what it is to wait.

We picture trips as entirely centred on momentum — all the new places we’ll see and visit — but it’s waiting you wind up doing the most of, in between the bursts of experience. It’s waiting where you process all it is you’re taking in.

We wait in narrow alleys for tables in trattorias, pressing up against the warm bricks of buildings too old to get our heads around to make way for scooters, tearing through. We wait to get into the Pantheon and then watch people who’ve also waited sit and scroll though the photos they just took of the Pantheon’s interior while they’re still in it. We wait for the clouds we’re at eye level with on Mount Etna to clear, our guide’s cheerful voice cutting through the milky vapour, telling us not to move too much in case we accidentally walk off the volcano. We wait for the lights to go down in Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, the both of us holding our breath. On Ischia we wait for the city bus at a stop flanked by a wall of wild fig trees, prickly pear bushes and a sheer drop down to the chalky blue sea, 100 ft below. In Palermo I wait on a back pew in an ancient church for the mea culpas and amens, the bowing, kneeling and crossing, of the handful of other people at early morning mass, so I can pantomime their rituals. We wait for our turn at a lot of coffee counters.

I wait between strikes of lighting I watch spearing down into the Gulf of Naples, glowing streaks of lurid purple and pink. I forget to count but don’t need to, the thunder so close on lightning’s heels, dark clouds tumbling over the pastel apartment stacked hills of Soccavo. In the narrow laneways below come staccato, explosive pops. The air feels charged.

This waiting is different. My body in the waiting’s thrall, lightly frightened and gently tensed, anticipatory. I keep lifting my pen to write, or moving to get up and crank shut the windows where rain is beginning to beat against the glass but forget to, eyes rapt on the sky out over the sea. This waiting, not exactly a pleasure, but with a rough thrill to it. The human will to stare wide-eyed at existential force from a distance, to wait out the storm.

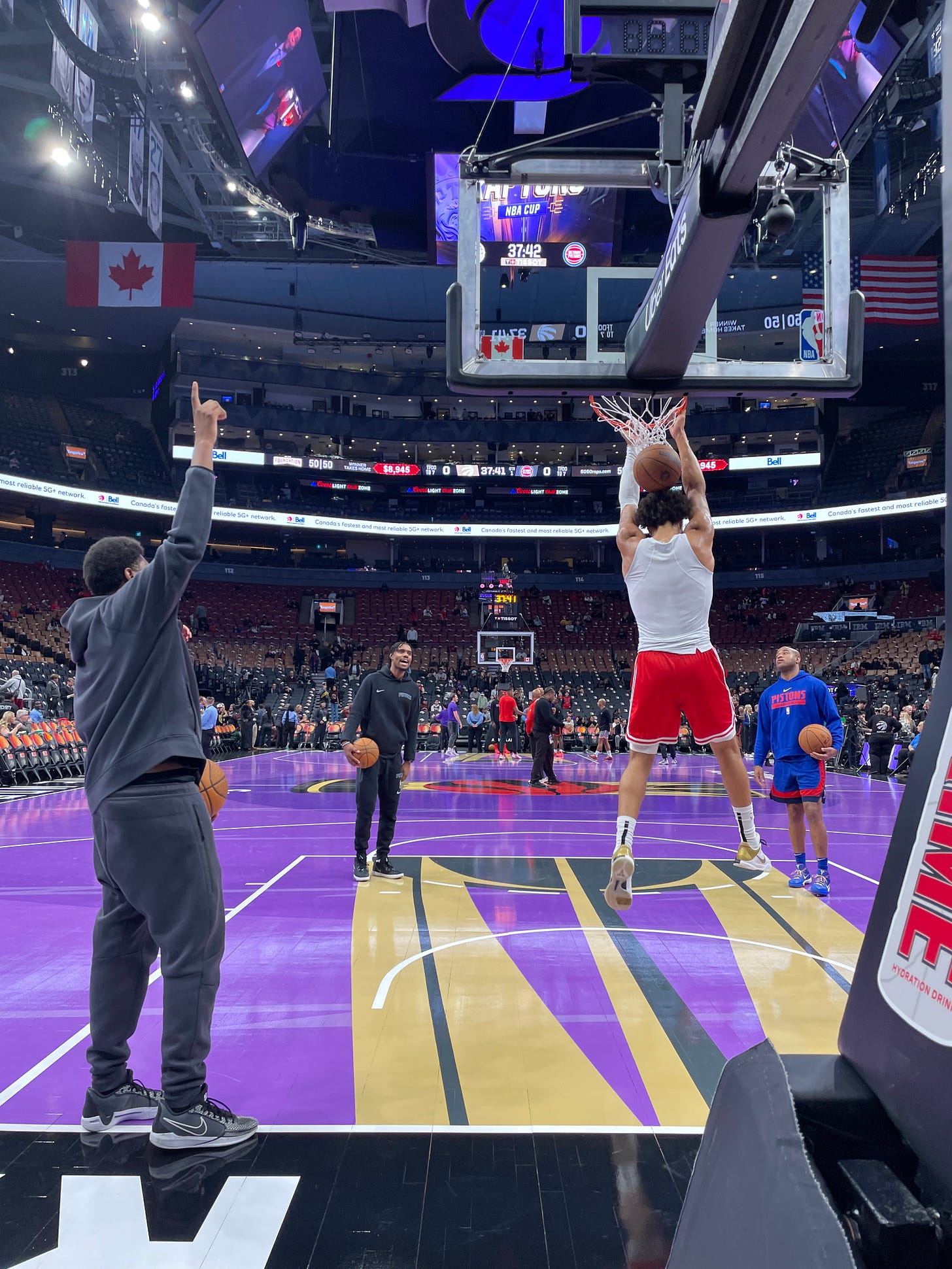

When I watch pregame warmups from the baseline I’m not focused, at least not entirely, on the shooting mechanics of Cade Cunningham. I’m thinking about the fluidity with which he and Jalen Duren move around each other — also Duren’s sweatpants, cut into DIY capris — and how Cunningham tends to wait a second longer, giving the ball a half rotation in his palm or rolling his shoulders back, before running the repetitive sequences his ask for. Or when I watch Bruce Brown run cross-court sprints, rehabbing his knee, and see how his eyes move around the arena and the people in it as he goes, I’m watching his trainer watch him while thinking about timelines: where they align, where they veer away.

I’ve watched Kevin Durant do split-squats while balancing a big cylindrical weight filled with water and wondered how far the equipment manager had to go in the arena to find an industrial sink to fill it. Watched Luka Doncic lob backwards trick shots from half-court while his coaches hooted with delight and thought about creating little cultivations of joy, night after night. Waited for end of warmup free throws because most culminate in a player dunking and swinging slow like a pendulum from the rim, how good that must feel, every muscle at your leisure.

I’m thinking about the kids in the stands early, screaming names of guys every few minutes, how soft spoken J.B. Bickerstaff was in his pregame that he turned the phrase “get out the mud” into tender instruction. That I should have worn a different belt, or how disorienting it feels to know so little about the current Raptors roster now so many seasons gone from the heart-deep familiarity of the championship team, or how much has changed over the last year across the parts of my life that felt comfortably known and set.

As much as I might want a game to start or finish, for someone to come and speak to a room so we can all go home, the waiting is the closest I’ve come to inhabiting borrowed time. A funny little antechamber between what’s happened and what’s about to I’m either crammed into with other people, or taking a moment in for myself.

It’s not that I’ve learned to hold so dearly to being in a over-warm locker room filled with competing voices and tinny tracks playing out of phones, while I pick my way around legs plunged into makeshift mop bucket ice tubs and people reclined on portable treatment tables and wait patiently, say, for Klay Thompson, it’s that entire universes unfold within the waiting that I would not be experiencing otherwise. As funny, frustrating or mundane, nerve-racking and hopeful those universes, each can feel momentarily sacrosanct. I try not to forget it.

This was lovely.

Delicious. You truly savor your subject and pass on the pleasure. Sent me down memory lane of my swimming career, a sport that undoubtedly involves even more waiting and locker-room intimacy.